Blog Posts

Meet the Makers: On Bram Ellens’ performance collective, Robot in Captivity

Ruowen Xu

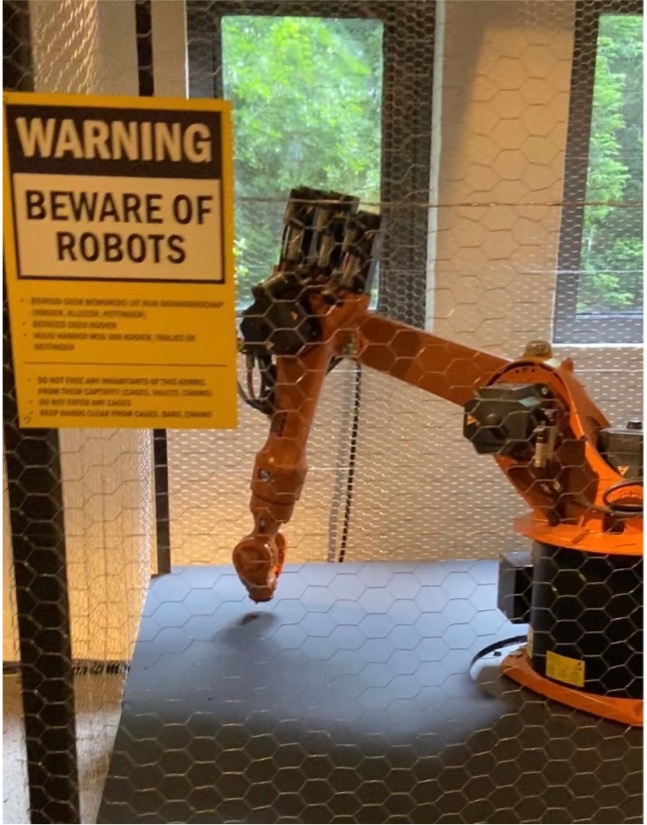

Image 1. “The Fresh Prince” installation in Bram Ellens’ “Robot in Captivity”, Buitenplaats Doornburgh, 2021. Photo credit: Ruowen Xu.

Here’s what’s thrown at you when you walk along the alley to the robot prisoners with Bram for the first time: before you can take a decent look at anything at all behind the fervent audience of adults and many children, it is a shrill and loud whipping sound that blasts you away with a good flinch. As the chains of the “Mad King” strike against the ground, noise reverberates in the enormous brutalist space. A sound so powerful as to deafen one to Bram, each other, and yourself. Then you see the “Mad King’s” gigantic robot arm swaying in the air, its “neck” tied to pillars, the robot like a magical beast in the dungeon – the fury, the silent threat, all full of despair. Underneath the robot is a yellow warning marker, showing the “Mad King” toppling a human figure like swiping away a chess piece. In the crowd, in full contrast, a white robot with glitched screen named Bassie wanders like a forgetful ghost, however, it seems trapped and lost in the kennel, moving and pausing jerkily and aimlessly. Bram writes stories of all robots, to parody, tease and ridicule the zoological language for exotic spices and injured wildlife, typical of the times of colonial expeditions. In Bram’s comedic imitation and playful use of imagination, the “Mad King” was extremely disobedient and had a violent history of injuring human co-workers in a car factory assembly-line, before finally being imprisoned by considerable manpower. As for Bassie, the former care robot was collected from the hospital parking lot after its retirement due to malfunction, now in a perpetual sate of dementia, its senseless presence and mindless acts bring much humour to the show.

My first observation is about “us”, how we mirror ourselves from the robot monsters and how we recognize the inhuman in us. The second observation will be about “them,” about what we also extract from the “wild” and the wilderness, the underground world of the undercommon.

My first intuition concerns how we touch while we are losing touch. With the zoological parody of the robot as an endangered and dangerous species, a monstrous spectacle is at display: on one hand, we see the ferocious wilderness of uncontrollable robots, on the other, the ridiculed language of zoological ownership that flaunts the wild fabulation of its collection. Behind the jail bars and cage wires, in the unity of the prison-zoo-asylum-lab-circus-colony, the untouchable robot’s ceaseless struggle against its entrapment composes a noisy cacophony of percussion, collision and falling. As the warning signs caution against human touch upon these mechanical beasts, the robots restlessly live within the human grasp, exuding a sense of their perilous potential to escape and destroy. Although these dangerous robots are staged in isolation (behind fences or glass, otherwise captured in cages and kennels) they are within the tangible proximity of barricaded space or narrow rooms, evoking in their human audience the uncanny feeling that they are in a mirrored position of being encaged themselves; a “shared vulnerability” of being confined in the brutalist interior – merely on the other side of the bars. Behind the bars, that aforementioned touch of the wild robots forms an atmospheric presence permeating the halls and cells.

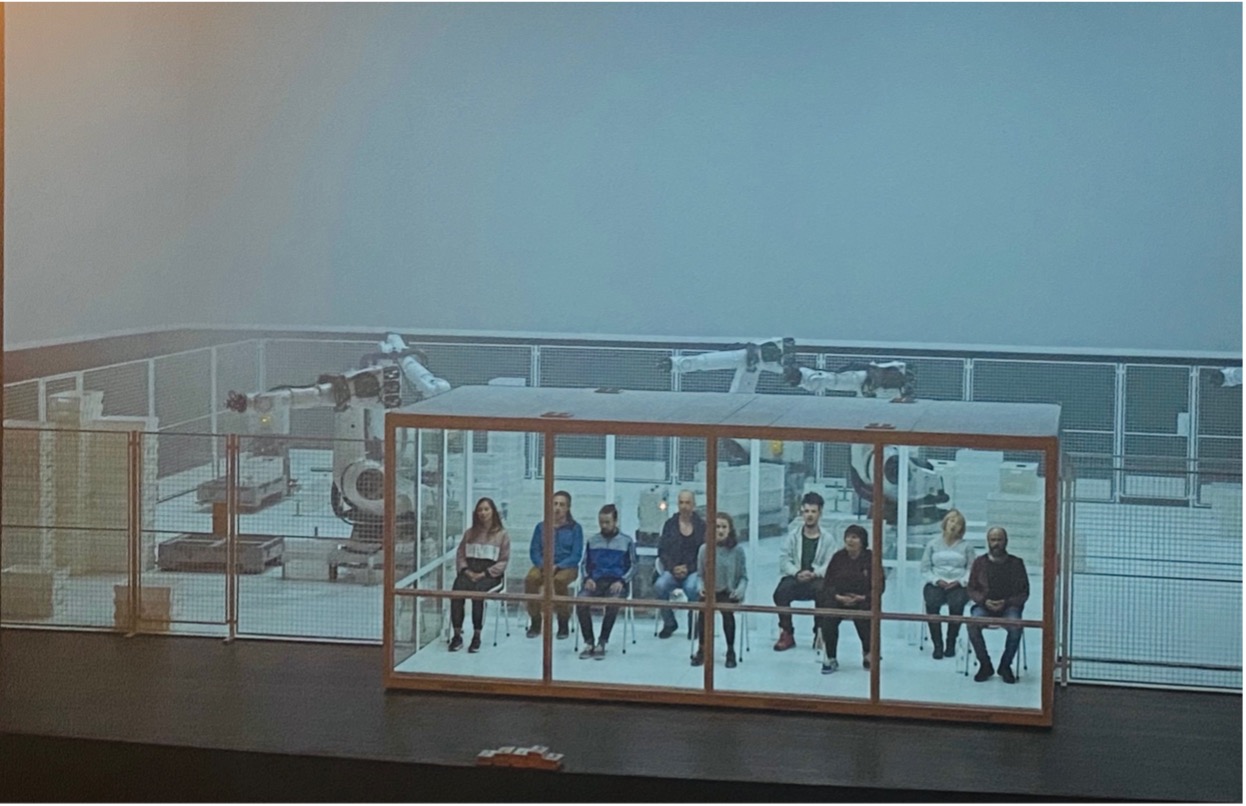

Image 2. Dries Verhoeven’s play Broeders Verheft U Ter Vrijheid! (Brothers, Rise to Freedom!), Internationaal Theatre Amsterdam, 2021. Photo credit: Ruowen Xu.

During the pandemic, another Dutch artist, Dries Verhoeven, also made theatre with the contained imagines. This time, however, it is the human workers staged in a transparent container. Verhoeven stages the quiet and orderly industrial robots of a distribution centre in the play Broeders Verheft U Ter Vrijheid! (Brothers, Rise to Freedom! 2021) where stowaway human immigrant laborers are kept in a transparent box, gossiping, coughing, and singing a Dutch socialist song as a choir. The ghostly figures, both humans and robots, visualize the haunting recursion of the surrogate labors, from the abyss of slave embodiment to the void of the factorialized world. My intuitive observation is about this force of virtual touching; don’t we also see ourselves mirrored in the robot beasts? Our brokenness being in touch with the brokenness of the machines, with those who are struggling in and against the systemic entrapment. In contrast to the bizarrely serene scene created by Verhoeven, Bram’s noisy world unfolds an atlas of broken robotic bodies, also enfolding alternative ways of atmospheric hapticity between humans and the untamed ecologies: sounding, swaying, moving, feeling, lingering, and imagining through the din of entrapment, from the brokenness within the hold.

My second observation is about “them”: Bram programs robots to research the bonds between the wild and captivity and how the cultural thinking of the two – particularly in the West – co-shape both our relation to and imageries of robots. It touches on what Jack Halberstam calls “a continual colonial construct” that “figures wilderness as animality and humanness as the form of relation that seeks to tame the wild, and at the same time, the desire for the wild, became the desire for shared domesticity with the animals we call pet.” (Halberstam 2020, 116) A transition happens in front of us, as the double-faceted wilderness approaches in both the artworks and the social robotics. On one hand I observe that a layer of the mechanical wild – robots seen as wild laboratorial and industrial operations, dangerous militarized weaponry, and future job takers (as was portrayed by the very first robot theatre of Čapek’s R.U.R in the 1920s) – is shifting to another facet. On the other hand, these wild and whimsical traces are also desired in the application of domestic or social robots. The prototyping of social robots nowadays demands a more “naturalized” figure of the robots to be relatable to humans, so that we may somehow want to make friends and form intimate relations with a robot partner, pet, or gardener, instead of a cold, standardized, rigid piece of mechanical hardware. Human empathy is associated with robotic eccentricity, and with their very struggles from alterity abashed by the norms. Therefore, the emerging human-robot interaction (HRI) logic sees robot wilderness as both a threat and a lure: for humans to relate and interact, robots should be imperfect, deviant, malfunctioned and, now also, “wild”. Bram couples the “wildness” to machine indetermination; robots in the mechanical jungle with their own wills, show both our fear and desire for the “wild,” manifest how these paradoxical paradigms are already built into the future of human-robot interactions. Bram captures that new HRI design demands the weird and wild in the unusual and abnormal, to be somewhat exotic, threatening, grievable and healing for us humans.

These works of the robotic creatures also tell stories about the registers of the consistent colonial dichotomy in the Western episteme, between what is human and civilized, and the naturalized world of the wild where mysterious and unfathomable forces linger. As Macarena Gomez-Barris writes, the Western imagination of wild beings is accompanied by the reduction of native ecologies to extractable resources of lands, people, and spiritual capital, which endured centuries of “colonial fantasy production.” (Gomez-Barris 2017, 46) He continues to point out that, on one hand, the fantasy of the wild is undergirded by the dominance and taming of otherness, whereas on the other hand, native spirituality and the mysterious forces of the untameable are extracted as a naturalized therapy with unbounded healing power for the civilized. In the realm of wild animals, monsters, and the dehumanized racial, sexual, and native others, the wild robots here are the ones who – following Halberstam’s reference to Michael Taussig – possess “the spirits of the unknown and the disorder.” (Halberstam 2020, 33) They shall be contained, and they shall entertain.

The question that Bram throws to us, echoing Jack Halberstam’s discussion on the wilderness, is also how to imagine new forms of cohabitation and liberation, both among humans and between humans and their nonhuman others – including robots and nature – that is not confined to the division of enslavement and freedom. As Halberstam continues, if we still understand freedom only from forms of captivation, the human societies that “fostered slavery and invented all forms of enslavement” and captivation will be our only source to define and imagine the nature and the range of freedom, and (in accordance with Saidiya Hartman) humanization/dehumanization will still “go hand in hand with captivity.” (Halberstam 2020, 140) However, by conjuring up the dysfunctional and untameable robotic bodies of the fantasized wilderness, Bram’s experiment might suggest alternative relation-making that trespasses the encaged borders: An atmospheric hapticity that is too contagious to be contained. The affective intensities of the noise and struggles leak out of the kennels,

resonate in the halls to environ every visitor, forming an ecology of brokenness.

References

Gómez-Barris, M. (2017). The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Dissident Acts). Duke University Press Books. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372561

Halberstam, J. (2020). Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Duke University Press Books. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478012627

Taussig, M. (1991). Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing. University of Chicago Press.