DADeR

[DADeR/Materiality] “Materiality, Improvisation, and Performativity in Robotic Musicianship” – Melanie Stahlecker

Concepts: materiality, improvisation, performativity

Case Study: Shimon robot

Abstract

Through an examination of “Shimon” the marimba-playing robot, this paper specifies the importance of materiality, improvisation, and performativity in robot design and argues that designing the robot to be human-like can improve its musical performance as well as enhancing its collaboration with humans. Producing good music is a complex, creative process that requires much attention to details. This includes training the robot’s artificial intelligence, developing facial expressions and body language, and considering adequate materials for the instruments it plays.

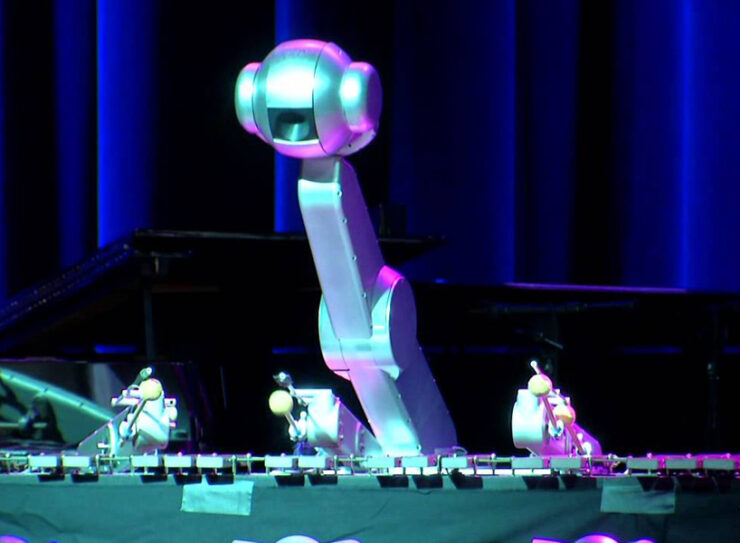

Shimon the Musical Robot. Image by Mike Murphy / Quartz

Robots are getting more evolved and being used for more different tasks every single day. Robots can have many different looks, capabilities, and functions. These functions and capabilities could be business-related, but robots could also have certain social and creative capabilities and functions. After seeing the NAO robots in real life, it became clear to me how these robots could fulfill certain social functions, for example in hospitals to help and talk to children, but also as a motivating workout buddy after sitting down at your desk for long period of time. Something else that really struck me was how robots are able to make music. In a TED Talk, Guy Hoffman explains how he and his team began to develop this robot that is able to improvise to jazz music with the help of artificial intelligence (AI).[1] As a musicologist, with a big interest in music cognition, this topic really intrigued me.

When first seeing this robot, improvising to jazz music on the marimba, I was extremely impressed. After this, however, one of the first things that came to mind was how certain musical aspects here could be improved or changed. Even though this music-making robot is already extremely impressive, an important aspect when playing any instrument is to play with feeling. For this ‘feeling’ aspect, there are different features to take into account, such as timbre, dynamics, movement, embodiment, but also materiality and performativity can be important factors here.[2] The two topics that will mainly be focused on in this paper are improvisation and materiality. These topics will be discussed with the help of subtopics and different sources about robotics, AI, music, and instruments. An interesting question that I will pay attention to here, is whether music-making robots, such as the one mentioned before, should be more or less human-like to really get the most out of the music and performance.

As mentioned before, materiality is an important aspect when it comes to musical instruments. Every type of material has the ability to create a different sound. There are many different musical instruments made out of different materials. Most instruments, nowadays, are made out of wood or metal, but there are also newer synthetic materials, which keep developing.[3] Before these more modern times, animal parts, such as guts, skin, and bones, were often used.[4] Animal skin is still used for percussion instruments, but not as much as some years ago, since a lot has been replaced with plastic or other synthetic materials.[5] When talking about this creation of different sounds, there are many factors that play a role here. Using different materials could result in a different frequency, pitch, timbre, loudness, and tone quality for example.[6] One way to see and research this is by comparing the sine waves of the sounds that these different materials would make.[7] Even when using the same materials, the sounds can be different. This is usually because the materials are used or struck differently, or because the tension of the material is different. Changing the way in which the material is used or struck could mostly influence the loudness or timbre of the sound.[8] Changing the tension of the material, however, usually changes the frequency of the sound, which gives it a different pitch.

Besides materiality, improvisation and performativity are two other important, and also related, terms that should be discussed in this paper. When talking about improvisation, this could be split up into two different segments, namely, individual improvisation, and improvisation with others. Individual improvisation is very much about creativity and skill, whereas improvisation within a group also consists of a certain level of communication.[9]

For individual improvisation, it is necessary to have the right skillset and knowledge about what you will be playing.[10] This is mostly knowledge about scales and chord progressions, to be able to know what will sound good and what will not. Creativity is also extremely important, since it can get boring if you would repeat the same thing over and over again while improvising. Some variation is always good when it comes to improvisation.[11] With improvisation in a group, it is needed to be able to anticipate what others will be doing while jamming or playing a song.[12] If a band is in the middle of playing a song, it is difficult to communicate using verbal language, since the other band members will not usually be able to hear what is said. So, instead of using verbal language, it is way more functional to use body language and facial expressions while improvising in a group.[13] With something as simple as giving someone a certain look, or a nod perhaps, it is easier to communicate with other band members, and to let them know when they need to jump in, when someone is done playing a solo, or when things need to be accented, for example.[14]

Not only improvisation, but performativity plays an important role here as well. When discussing the term ‘performativity’, Bleeker and Rozendaal mention that “performativity is not a matter of what an object does per se (its performance) but describes what this doing brings about within the given situation.”[15] To get to know more about this, it is necessary to start understanding more about this ‘object’, but also to take a look at the connections and relations to others in its surroundings, and the role it plays here.[16] Of course, this is very broadly speaking, but it could be applied to many different objects and situations. In the discussion of performativity and music, Jane Davidson argues that “performativity in music demands that we explore what is embodied, and also brings to the fore the socio-cultural environments in which performances exist.”[17] Both of these definitions or clarifications of performativity, both generally speaking, as well as focused on performativity in music, seem to be a lot about exploring and understanding the specific embodiment it is about. Performativity could be seen as some kind of experience, and it could refer to many different things, such as persona, reception, improvisatory practices, and more.[18]

Since this paper is mainly about music-making robots, it is good to start looking at examples of such robots in relation to materiality, improvisation, and performativity. An important example of a music-making robot is Shimon, the robotic marimba player.[19] Before actually creating Shimon, Guy Hoffman and Gil Weinberg, the two who came up with the idea for Shimon, created a smaller and more portable version of Shimon, called Shimi.[20] Student Mason Bretan helped by “developing machine learning based improvisation and emotional gestures” for both Shimi and Shimon.[21] He also helped to develop a musical robotic prosthetic, to help amputee drummer Jason Barnes play the drums again after his accident where he lost his arm.[22] Besides these, there are many other robotic musicians, that include many different instruments, such as percussive instruments, stringed instruments, wind instruments, and even some augmented and novel instruments.[23] Out of all these different examples, however, I will mostly be focusing on Shimon, the improvising marimba playing robot, since Shimon is quite well-developed, and definitely most well-known.

Shimon was first developed in the early 2010s. In October 2013, Guy Hoffman, co-creator of Shimon, hosted a TED Talk where he introduced Shimon in its early stages.[24] Ever since then, Shimon has experienced quite the development, which allowed Shimon to become a touring robotic musician, with its own album, released in 2020.[25] And he can even be seen in an episode of The World According to Jeff Goldblum on streaming platform Disney+.[26] When looking at its design, Shimon used to be just an “expressionless metal ball on a mechanical arm” but has had somewhat of a makeover and now has eyebrows, a mouth, and is able to move its head, which all contribute to Shimon’s way of communication.[27] Shimon also has four arms, with two solenoid-driven marimba mallets on each arm, so eight in total, to be able to strike the keys when playing the marimba.[28] The material that is used here is the same as what is usually used to play the marimba, which allows Shimon to recreate the same kind of sounds that human marimba players could make.

When discussing improvisation and performativity in Shimon’s situation, the builders of the robot had to take into account that Shimon can do this with artificial intelligence (AI).[29] Since there are some limitations when it comes to the use of AI, Shimon had to be trained to learn how to improvise and communicate with others onstage.[30] After learning how to do this, Shimon was able to improvise within a call and response interaction, which means that someone would play something and Shimon would respond to this by playing something else.[31] Now, after quite some years, Shimon’s AI has been extremely developed, to the point where Shimon can now come up with its own songs, and even with its own lyrics.[32] Not all of Shimon’s lyrics make complete sense, however, because of AI’s limitations.[33] But to be fair, quite some human musicians’ lyrics do not even make sense either.

With every robotic musician, materialism is of great importance. The specific materials that are used are what makes the sounds when playing instruments so different. Hitting a metal key with a wooden object can create a different sound than hitting the same metal key with a metal object, or any other type of material.[34] For certain instruments, such as drums, it makes sense to just use drumsticks, as for marimba it makes most sense to use the mallets, since these would be used to play those instruments anyways.[35] When thinking of stringed instruments, it makes sense for a violin to use a bow, but with something like playing a guitar, this use of material might be somewhat more complicated.[36] This is because a guitar is often played by using your fingers. Since a robot is not made out of flesh and bones, like humans are, it could be more difficult to imitate this sound, which results in having to look for an alternative type of material that could sound similar to when a human is playing the instrument.[37] Although, since music can be extremely experimental nowadays, it might also be a good approach to just use a different type of material and purposely make it sound different than what it would sound like if a human would be playing it.[38] Playing around with this use of materials could result in a different timbre, frequency, and loudness, which could make this a more interesting approach.[39] Most people, however, would probably prefer the more human-like approach, since this sounds most familiar to them. It is often this familiarity that people are looking for, that makes us want to see robots that are more human-like as well.[40]

Trying to make robots more human-like also applies in the aspects of improvisation and performativity.[41] As mentioned before, communication is crucial when it comes to improvising in a group, and it is essential in getting a specific message across to an audience as well.[42] Training a robot, or a robot’s artificial intelligence, in recognizing and imitating people’s expressions, body language, emotions, and way of communicating in these situations would make most sense.[43] This way, the human-robot interaction would be made easier and clearer, which results in humans and robots being on the same page during the improvisation. Shimon could be seen as an excellent example here, since this robot has enough features to show its facial expressions, but also uses its body language to move on the beat, and Shimon even moves its mouth when it speaks or sings.[44] Even though Shimon does not have all of our human features, there sure are enough human-like features for Shimon to be able to communicate almost exactly like humans would.

After discussing the topics of materiality, improvisation, and performativity in relation to robotic musicians, it became clear that there are not always simple answers to be found, and that some aspects are more about preference. When it comes to materiality, the use of materials in designing these robotic musicians entirely depends on what the goal for the robot is, and what kind of sound it should realize. What makes the different materials sound different is a somewhat more complicated physical science matter but can be seen and heard in certain musical aspects, such as timbre, loudness, pitch, and tone quality.[45] Since a good balance between familiarity and novelty often guarantees most success in music, it seems best to let the robot reproduce sounds on the chosen instrument that are not too far off from what it would sound like if humans played that same instrument.[46] A second argument here is that the robot’s artificial intelligence needs to be trained, for it to be able to play the instrument properly and produce something that sounds relatively good.[47]

In improvisational skills and performativity, this would be the same case. It is easiest if the robot would be trained to act as human-like as possible, in order for it to communicate easily with its fellow, human, bandmates.[48] After getting to know so much about robotic musicians, it has become clear that there is already a lot developed in this specific field of research. There is, however, still much more to be discovered and developed. Shimon is a great starting point to start exploring more ways of designing robotic musicians, perhaps with different instruments, or maybe even multiple instruments at the same time. It is also very interesting to see how far Shimon can get with the power and abilities of AI used for songwriting. Would it be possible for Shimon to produce some actual hits, if Shimon would be trained accordingly? To what extend can Shimon’s lyrics and musical improvisational skills make sense? And is Shimon able to create a bigger fanbase, only with its own songs? These, and other questions, would be interesting to answer in follow-up research on robotic musicianship.

.

[1] TED, Guy Hoffman, “Robots with “Soul”,” October 2013, https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[2] Gil Weinberg, Mason Bretan, Guy Hoffman, and Scott Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship: Embodied Artificial Creativity and Mechatronic Musical Expression (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020), vii-viii, 11.

[3] Neville Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” Acoustics Australia 40, no. 2 (2012): 131; Ze Hong Wu, and Jia Hui Li, “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making.” Materials & Design 89 (2016): 660.

[4] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130-131.

[5] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130-131; PETA, “Do Musical Instruments Utilize Animal Products?” 2022, https://www.peta.org/about-peta/faq/do-musical-instruments-utilize-animal-products/.

[6] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130-133; Wu and Li, “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making,” 661-664.

[7] Wu and Li. “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making.” 660-662.

[8] Gil Weinberg, Mason Bretan, Guy Hoffman, and Scott Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship: Embodied Artificial Creativity and Mechatronic Musical Expression, 4, 13, 51, 58, 218.

[9] Steven Kemper, “Locating Creativity in Differing Approaches to Musical Robotics,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 8 (2021): 1-3; Anthonia Carter, Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri, and Guy Hoffman, “Lessons from Joint Improvisation Workshops for Musicians and Robotics Engineers,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 7 (2021): 9; Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, vii, 13.

[10] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 50.

[11] Ibid, 89.

[12] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 13, 90; TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[13] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 17, 93; TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[14] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 42; TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[15] Maaike Bleeker and Marco C. Rozendaal, “Dramaturgy for Devices: Theatre as Perspective on the Design of Smart Objects,” in Designing Smart Objects in Everyday Life (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), 48.

[16] Ibid, 48.

[17] Jane W. Davidson, “Introducing the Issue of Performativity in Music,” Musicology Australia 36, no. 2 (2014): 179.

[18] Ibid, 180.

[19] Guy Hoffman and Gil Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” Autonomous Robots 31, no. 2-3 (2011): 133.

[20] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, Ix.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, x.

[23] Ibid, 4-9.

[24] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[25] Shimon the Robot, Shimon Sings, 2020, Spotify, https://open.spotify.com/album/49mqgxoLXFGP5NnBB5PQAU?si=eje-lQO1TveP9ZAF53LL0w.

[26] National Geographic, The World According to Jeff Goldblum, Season 2, Episode 7: “Puzzles,” 2022, https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/video/592aaee0-57b7-4cf1-8f7c-945fbe2921aa.

[27] Luana Steffen, “Shimon, the Robot Musician, Is About to Release His First Album,” 8 March 2020, https://www.intelligentliving.co/shimon-the-robot-musician-is-about-to-release-his-first-album/.

[28] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 5, 31-37.

[29] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

[30] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul; Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 15-16.

[31] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul; National Geographic, The World According to Jeff Goldblum, https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/video/592aaee0-57b7-4cf1-8f7c-945fbe2921aa.

[32] Steffen, “Shimon, the Robot Musician, Is About to Release His First Album,” https://www.intelligentliving.co/shimon-the-robot-musician-is-about-to-release-his-first-album/.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130-132; Wu and Li, “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making,” 660-664.

[35] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130; Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 31-37, 52, 193-196.

[36] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 131.

[37] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, vii-viii, 7, 52; Hoffman and Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” 134.

[38] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, vii-viii.

[39] Ibid, vii, 11.

[40] Ibid, vii-viii.

[41] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, vii-viii; Hoffman and Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” 134, 150-152.

[42] Hoffman and Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” 133.

[43] Ibid, 150-152.

[44] Hoffman and Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” 150-152; Steffen, “Shimon, the Robot Musician, Is About to Release His First Album,” https://www.intelligentliving.co/shimon-the-robot-musician-is-about-to-release-his-first-album/.

[45] Fletcher, “Materials and Musical Instruments,” 130-133; Wu and Li, “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making,” 661-664.

[46] Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, vii-viii.

[47] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul; Weinberg, Bretan, Hoffman, and Driscoll, Robotic Musicianship, 15-16.

[48] TED, “Robots with “Soul”,” https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul; Hoffman and Weinberg, “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player,” 15-16, 150-152; National Geographic, The World According to Jeff Goldblum, https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/video/592aaee0-57b7-4cf1-8f7c-945fbe2921aa.

Bibliography

Bleeker, Maaike, and Marco C. Rozendaal, “Dramaturgy for Devices: Theatre as Perspective on the Design of Smart Objects.” In Designing Smart Objects in Everyday Life, London: Bloomsbury, 2021: 43-54.

Carter, Anthonia, Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri, and Guy Hoffman. “Lessons from Joint Improvisation Workshops for Musicians and Robotics Engineers.” Frontiers in Robotics and AI 7 (2021): 1-15.

Davidson, Jane W. “Introducing the Issue of Performativity in Music.” Musicology Australia 36, no. 2 (2014): 179-188.

Fletcher, Neville. “Materials and Musical Instruments.” Acoustics Australia 40, no. 2 (2012): 130-133.

Hoffman, Guy, and Gil Weinberg. “Interactive Improvisation with a Robotic Marimba Player.” Autonomous Robots 31, no. 2-3 (2011): 133-153.

Kemper, Steven. “Locating Creativity in Differing Approaches to Musical Robotics”. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 8 (2021): 1-6.

National Geographic. The World According to Jeff Goldblum. Season 2, Episode 7: “Puzzles.” 2022. https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/video/592aaee0-57b7-4cf1-8f7c-945fbe2921aa.

PETA. “Do Musical Instruments Utilize Animal Products?” 2022. https://www.peta.org/about-peta/faq/do-musical-instruments-utilize-animal-products/.

Shimon the Robot. Shimon Sings. Spotify. 2020. https://open.spotify.com/album/49mqgxoLXFGP5NnBB5PQAU?si=eje-lQO1TveP9ZAF53LL0w.

Steffen, Luana. “Shimon, the Robot Musician, Is About to Release His First Album.” 8 March 2020. https://www.intelligentliving.co/shimon-the-robot-musician-is-about-to-release-his-first-album/.

TED. Guy Hoffman. “Robots with “Soul”.” October 2013. https://www.ted.com/talks/guy_hoffman_robots_with_soul.

Weinberg, Gil, Mason Bretan, Guy Hoffman, and Scott Driscoll. Robotic Musicianship : Embodied Artificial Creativity and Mechatronic Musical Expression. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020.

Wu, Ze Hong, and Jia Hui Li. “Carbon Fiber Material in Musical Instrument Making.” Materials & Design 89 (2016): 660-664.